From Validated Design to Enforced Architecture

Why Nutanix Infrastructure Manager appears late in the maturity curve.

Nutanix Infrastructure Manager arrived quietly with Prism Central 7.5. No launch campaign, no aggressive positioning, no immediate sense of urgency. At first glance, it is easy to misread it as just another management feature.

It is not.

NIM exists to solve a very specific problem. A problem that does not appear in small or simple environments, and that cannot be understood by looking at features alone. To understand why it exists at all, it is necessary to start from Nutanix Validated Designs.

This article comes out of a deliberate effort to study Nutanix Infrastructure Manager beyond the announcement and feature descriptions.

The intent is not to explain how NIM works, but to understand why it exists, when it becomes relevant, and what architectural problems it is actually meant to solve.

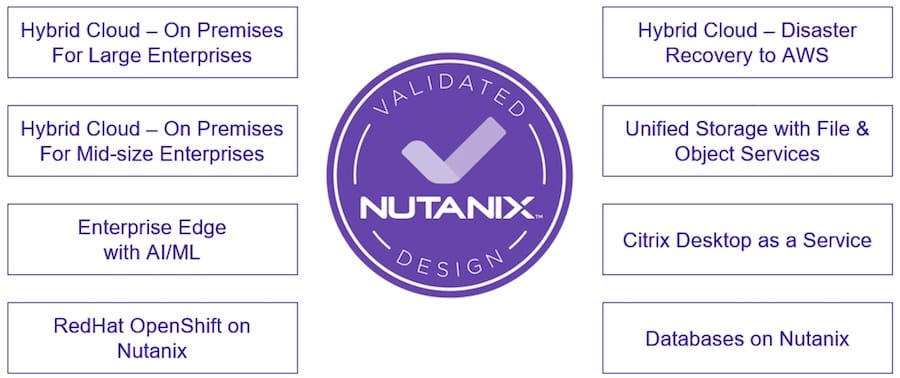

Nutanix Validated Designs Are Intentionally Few

One of the first questions that naturally arises is why the number of Nutanix Validated Designs publicly available is so limited. Seeing only a small set of designs often leads to the assumption that something is missing, hidden, or gated.

It is not.

Nutanix Validated Designs are not meant to be an exhaustive catalog of possibilities. They represent a curated set of architectures that Nutanix is willing to validate, support, and maintain over time. Each design targets a specific use case and comes with strict constraints in terms of Bill of Materials, lifecycle alignment, and architectural boundaries.

This is not an accident. Maintaining an NVD means validating not only deployment, but also upgrades, compatibility, and long-term supportability. That level of commitment makes scale impossible. NVDs must be few to remain credible.

Nutanix itself makes this explicit in the blog post Nutanix Validated Designs: Blueprints for Success, where NVDs are described as blueprints, not prescriptions. They define what a correct architecture looks like, not how it must be executed.

That distinction matters.

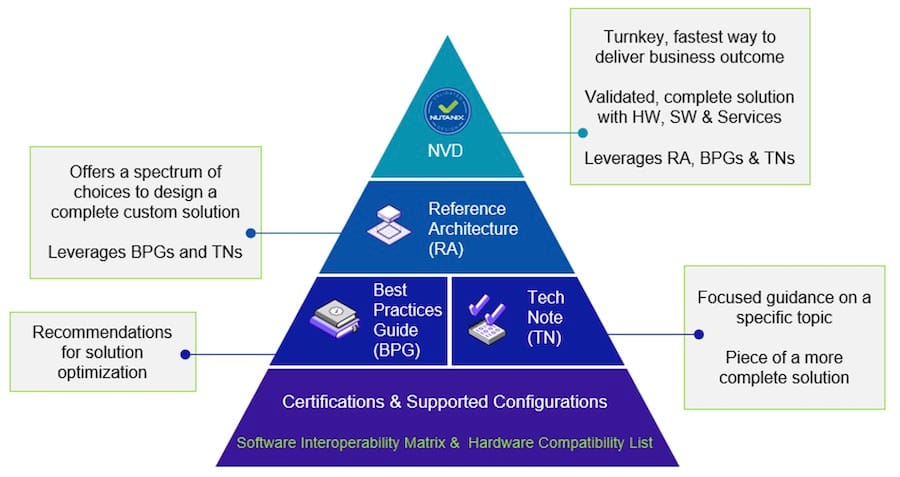

From Blueprint to Architectural Constraint

Validated Designs do not exist in isolation. They sit at the top of a layered validation model built on supported configurations, best practices, technical notes, and reference architectures. Each layer reduces ambiguity and increases assurance, until the design becomes something Nutanix is willing to stand behind as a whole.

This layered model explains both the rigidity and the value of NVDs. It also explains their main limitation. A blueprint can guide architecture, but it cannot enforce it.

As long as environments are small, human discipline is enough. Teams remember why things were designed in a certain way. Over time, as environments grow, that discipline erodes. Exceptions accumulate. Lifecycle diverges. The design remains valid on paper, but slowly disappears in practice.

This is the gap NIM is designed to address.

The Real Problem Nutanix Infrastructure Manager Solves

Nutanix Infrastructure Manager is often misunderstood because it is assumed to manage clusters or workloads.

It does not.

NIM exists to govern the management plane itself.

As environments scale, Prism Central instances multiply. They are deployed at different times, upgraded on different schedules, and often managed by different teams. Over time, the management infrastructure becomes fragmented and difficult to reason about.

At that point, the challenge is no longer managing clusters.

It is managing the management layer itself.

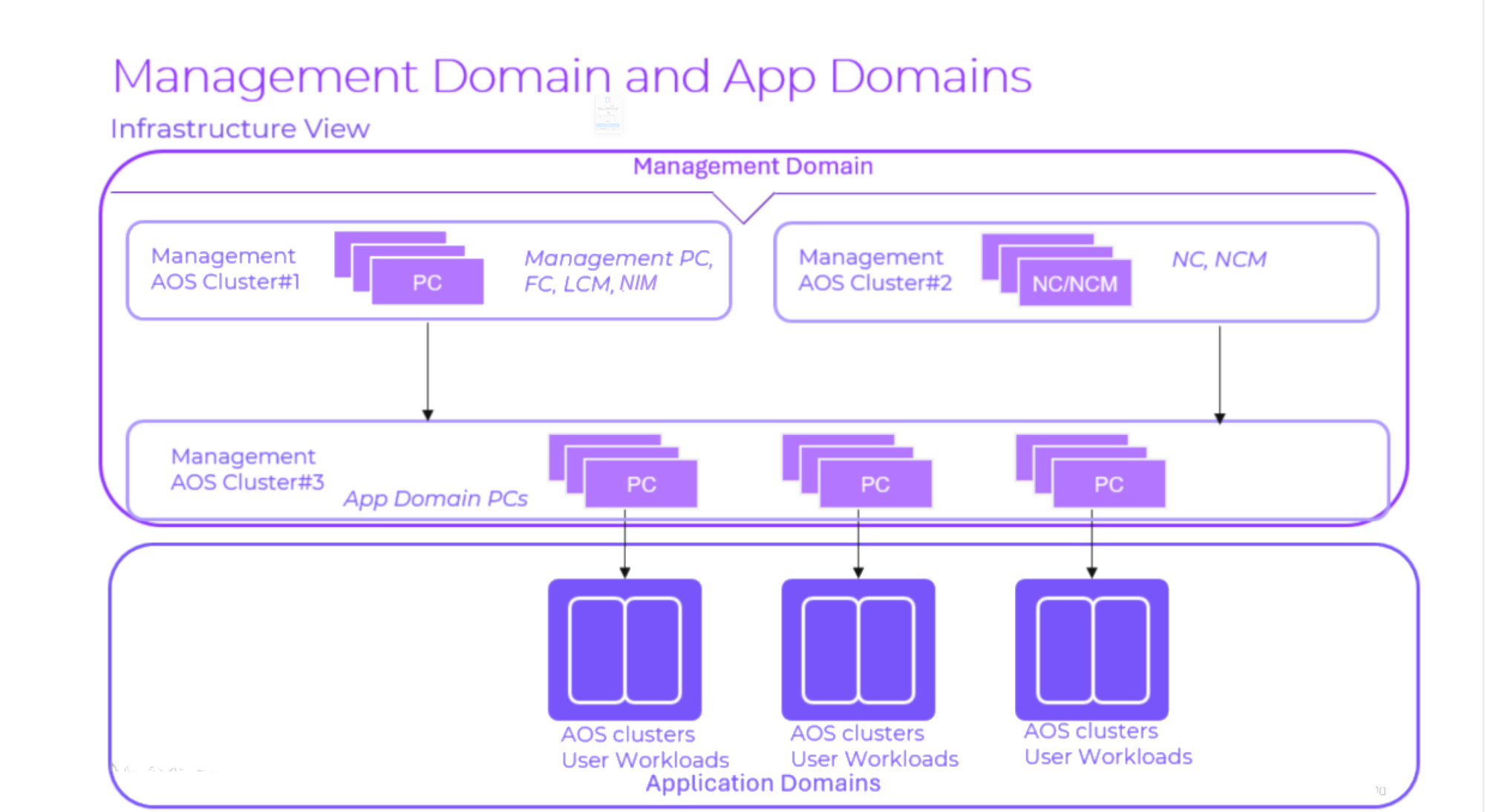

NIM introduces a formal separation between a Management Domain and one or more App Domains. This separation is not conceptual. It is architectural, structural, and enforceable.

NIM as an NVD Enforcement Layer

This is where Nutanix Infrastructure Manager and Nutanix Validated Designs finally connect.

NIM does not create architectures. It does not replace design guides or reference models. It consumes NVDs as authoritative input and enforces their constraints on the management plane.

Deployment, expansion, and upgrade of Prism Central instances are no longer left to individual interpretation. Supported BOMs, domain separation, lifecycle boundaries, and architectural roles become system-level constraints.

Without NIM, an NVD remains a blueprint.

With NIM, that blueprint becomes enforceable.

This is the architectural shift implied by the term enforced architecture.

What Really Belongs to the Management Domain

Once a Management Domain exists, a natural question follows. What actually belongs there?

The answer is more restrictive than many expect.

The Management Domain exists to govern the Nutanix platform itself. It is responsible for Prism Central orchestration, lifecycle coordination, and architectural compliance across domains. It does not exist to host services consumed by application teams.

This distinction becomes clear when looking at services such as Nutanix Kubernetes Platform and Nutanix Database Service.

Even though both provide management capabilities, they are platform services. They have their own lifecycle, are consumed by workloads, and scale according to application needs. For this reason, both NKP and NDB belong to the App Domain.

Placing them in the Management Domain would blur architectural boundaries, couple unrelated lifecycles, and undermine the separation NIM is designed to enforce.

In the NIM model, management infrastructure is not where services are managed.

It is where the platform itself is governed.

Single Prism Central and the Role of NIM

It is worth stating this clearly.

In environments running a single Prism Central, Nutanix Infrastructure Manager does not introduce meaningful architectural value.

This is not a technical limitation. It is a consequence of NIM’s purpose.

NIM governs relationships between domains. It orchestrates multiple Prism Central instances, enforces separation, and coordinates lifecycle across boundaries. With a single Prism Central, that complexity does not exist.

There is nothing to orchestrate, no lifecycle to coordinate across domains, and no architectural separation to enforce. The environment is already consistent by definition.

In these scenarios, Nutanix Infrastructure Manager is not missing.

It is simply premature.

Design Maturity, NMCID, and the NCX gate

Long before diving into Nutanix Infrastructure Manager, I had been carrying a recurring question.

Why is it not possible to move forward in the Nutanix Certified Expert path without first going through Nutanix Multicloud Infrastructure Design, especially considering the non-trivial economic barrier it introduces?

At first glance, it feels restrictive. Even arbitrary. Particularly for engineers with years of hands-on experience and real-world exposure to complex environments.

That question existed well before NIM.

What NIM provided was the context to finally understand the answer.

NCX is not designed to validate technical execution. It does not test how well someone knows a product or a set of features. It evaluates how architectural decisions are made, justified, and defended under constraints. In practice, it resembles a peer design review far more than a traditional certification exam.

Seen from this perspective, NMCID plays a very precise role.

It does not teach tools. It does not focus on implementation. It trains architectural reasoning. It forces a shift from solution-first thinking to constraint-aware design discipline. It establishes a shared language around trade-offs, boundaries, and long-term consequences.

This is exactly the kind of mindset NCX assumes, not teaches.

The economic barrier of NMCID is not incidental. It functions as a gate. Not for knowledge, but for intent. It discourages badge-driven progression and filters for architects willing to invest time and effort into disciplined design thinking.

This is where the connection with Nutanix Infrastructure Manager becomes clear.

An NVD defines what Nutanix considers defensible and supportable.

NMCID teaches how to reason about that design and understand when it can be adapted without breaking its assumptions.

NIM enforces those decisions once scale and complexity make consistency non-negotiable.

In this light, NIM is not just a management capability. It is the operational expression of a design maturity that NCX expects to already be in place.

Closing the Loop

Nutanix Infrastructure Manager is not a feature you enable when something breaks.

It is a consequence of architectural maturity.

If an environment still depends on flexibility, shortcuts, and human discipline, NIM will feel unnecessary or even restrictive. At that stage, validated designs remain guidance, not constraints.

NIM starts to make sense only when inconsistency becomes more expensive than control. When the management plane itself requires governance. When architecture must survive not just deployment, but time.

Seen through this lens, the question is no longer whether you need Nutanix Infrastructure Manager.

It is whether your architecture is ready to be enforced.