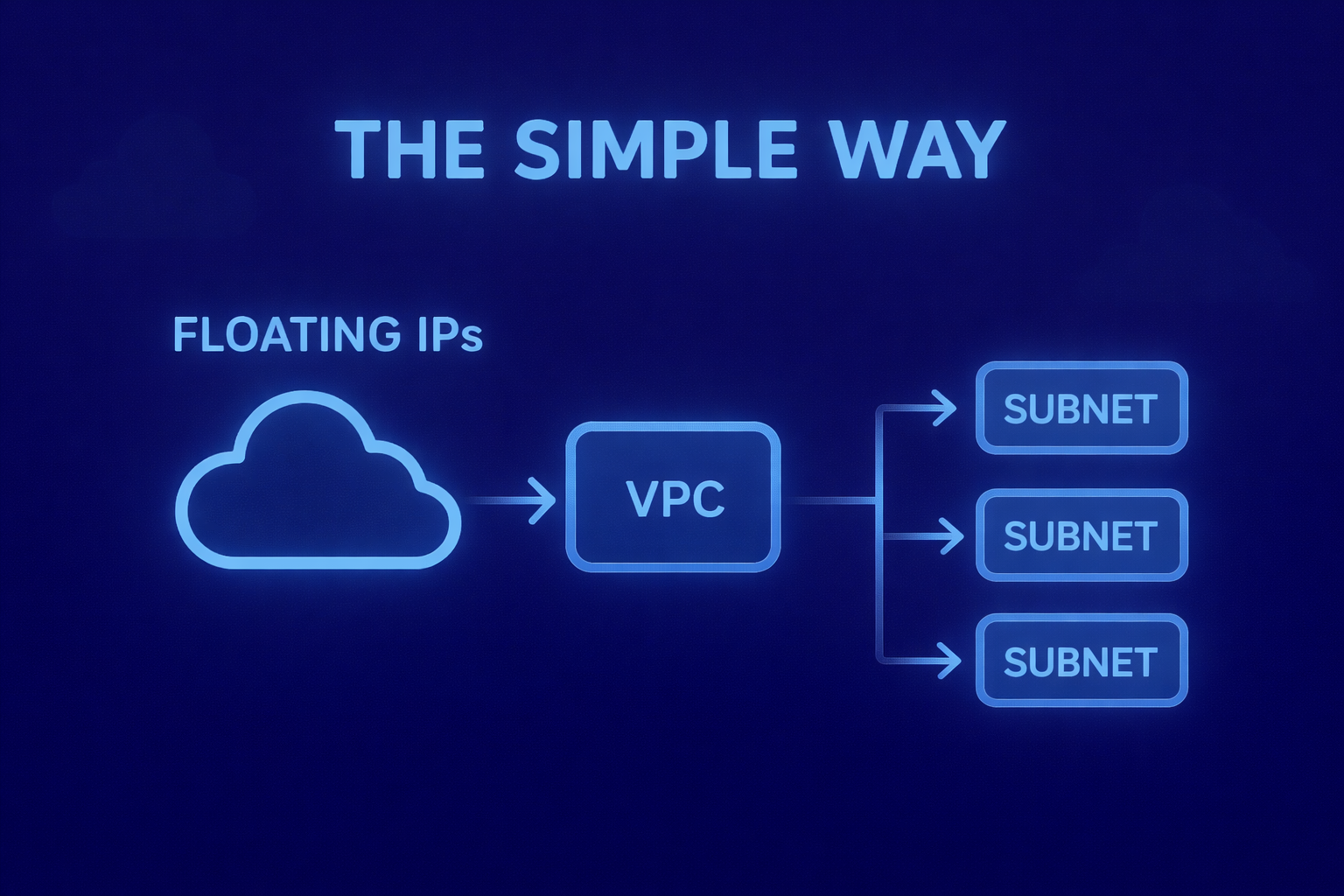

How to Save Public Floating IPs on Nutanix: The Simple Way

A single VPC design where subnets and microsegmentation avoid transit routing and floating IPs are assigned directly to workloads.

In the previous articles, I explored different ways to reduce public floating IP consumption on Nutanix.

In the first one, I focused on native constructs and standard VPC behavior, keeping the design close to the platform defaults.

In the second one, I pushed further, introducing a transit VPC and more advanced routing patterns to maximize reuse and flexibility.

Both approaches solve real problems. But after working through those designs in real environments, there is a third option worth discussing. One that deliberately avoids a transit VPC altogether.

This article describes a design based on a single VPC, multiple subnets, and microsegmentation, where floating IPs are assigned directly to workloads and isolation is enforced through policy rather than routing. It is not a simplification for edge cases. It is a pragmatic choice for environments where clarity, control, and operational simplicity matter more than architectural sophistication.

Choosing not to build a transit VPC

Transit-based designs are powerful, but they introduce an additional architectural layer whose primary purpose is traffic aggregation and routing control. When that requirement does not actually exist, the architecture starts to work against itself.

In many environments, there is no need to centralize routing logic, no requirement for traffic stitching across multiple VPCs, and no benefit in abstracting egress behind an additional hop. In those cases, the transit VPC adds complexity without adding meaningful value.

This pattern intentionally removes that layer. There is no transit VPC, no route forwarding, and no service insertion. The design relies on a single VPC, built with clear intent and minimal moving parts.

One VPC, multiple subnets, explicit roles

The foundation of this design is intentionally simple. A single VPC hosts multiple subnets, each with a clearly defined role.

Subnets are not used as a routing mechanism. They are used to express intent. Each subnet represents a specific exposure level, a trust boundary, and a functional scope. This makes the design easy to understand and easy to explain, even to teams that were not involved in the original architecture decisions.

Nothing is implicitly reachable. Reachability is always explicit and deliberate.

Isolation through policy, not topology

In this architecture, isolation does not come from network hops or routing tricks. It comes from policy.

Traffic between subnets is controlled through microsegmentation rules. Communication is allowed only where it is explicitly required, and denied everywhere else. Using Nutanix Flow, the network boundary becomes declarative. The policy defines what is allowed, not the path packets take to get there.

This removes the need to reason about intermediate gateways or forwarding behavior. The topology remains flat, but it is not open. Isolation is enforced logically, not physically.

Floating IP assignment becomes workload-centric

This is where the operational difference becomes very concrete.

With a transit VPC design, floating IPs are typically configured by selecting the transit VPC and associating the floating IP to an internal address. The routing path then determines how traffic exits the environment. In that model, the floating IP is effectively attached to the network path rather than to the workload itself.

With a single VPC design, the association changes completely. Floating IPs can be assigned by selecting the VM directly, or managed from the VM edit workflow. The floating IP becomes a property of the workload.

This makes it immediately clear which VM uses which public IP, why that IP exists, and which service depends on it. The relationship between workload and external identity is explicit and visible.

Why this matters operationally

This is not a UI convenience. In real environments, outbound identity often matters.

Common scenarios include third-party IP whitelisting, external APIs tied to a specific source address, and security reviews that require clear ownership of public exposure. When floating IPs are tied directly to workloads, identity is explicit, changes are localized, and troubleshooting is straightforward.

When floating IPs are tied to routing paths, identity becomes implicit. Debugging requires knowledge of the underlying topology, and small changes can have wider and less predictable effects. Reducing indirection reduces operational risk.

Saving public IPs as a consequence, not a goal

This pattern does not attempt to optimize public IP usage directly. It achieves it as a side effect of a clearer design.

Public IPs are consumed only where a workload truly requires external access, where that access is intentional, and where the association can be justified and documented. Most services remain private by default. No duplicated gateways are introduced, and no shared egress paths are forced.

Public IP consumption decreases naturally because fewer components need to be exposed.

When this pattern fits best

This approach works particularly well for enterprise application platforms, environments with clear service boundaries, teams that value operational clarity, and architectures that grow by services rather than by tenants.

It is not designed for heavy multi-tenant routing scenarios, network-as-a-service models, or environments where transit routing is a core requirement. Not every environment needs a transit architecture.

A note on what could come next

One final consideration is worth mentioning.

Having the option to manage this flow directly at the VPC gateway level with more granular capabilities would be extremely valuable. In particular, being able to handle use cases such as port forwarding without consuming additional public IPs would open up very practical design options.

In many environments, a single public IP combined with controlled port-level exposure would be more than sufficient. It would allow teams to keep the architecture simple, avoid unnecessary IP consumption, and still meet real operational requirements.

The patterns described in this series work well today within the current constructs. Extending the VPC gateway with richer ingress and egress capabilities would make these designs even more effective, without forcing architects to reintroduce complexity elsewhere.

Simplicity does not mean giving up flexibility. It often just means moving it to the right place.